Sorry, this entry is only available in Español and Français.

Category Archives: Documentos

My enemy’s brother. Aurelio SANZ BAEZA

Our heart workshop has tools for maintenance, to repair when there is a deterioration, to update or even to create good feelings. Sometimes we don’t find the tool, or they’re messy, or broken, or we need new ones that are hard to come by. We also sometimes use the wrong tool, because we think it’s easier to handle. The heart workshop may be damaged, leaky, or unventilated; it may be inadequate or not always be clean. It is likely that we have had times when the workshop was “closed for holidays”… In the heart workshop there are on a daily basis hurt feelings, distrust of others, wounded pride – our ego open to ridicule – and disappointments. Very different forms, shades and perceptions.

Our heart workshop has tools for maintenance, to repair when there is a deterioration, to update or even to create good feelings. Sometimes we don’t find the tool, or they’re messy, or broken, or we need new ones that are hard to come by. We also sometimes use the wrong tool, because we think it’s easier to handle. The heart workshop may be damaged, leaky, or unventilated; it may be inadequate or not always be clean. It is likely that we have had times when the workshop was “closed for holidays”… In the heart workshop there are on a daily basis hurt feelings, distrust of others, wounded pride – our ego open to ridicule – and disappointments. Very different forms, shades and perceptions.

I once heard a person tell me “Reeds become spears”, referring to the great disappointment of the “friendly nullity” of who I believed was a great friend. Having lost a friendship we can come that distrust not only that person, but others that we are unsure of. “Our heart must be cleansed, put in order and purified. Of what? Of the falsehoods that stain it, from hypocritical duplicity. All of us have these. They are diseases that harm the heart, soil our lives and make them insincere. We need to be cleansed of the deceptive securities that would barter our faith in God with passing things, with temporary advantages.” Pope Francis at Mass in Erbil, Iraq, 7 March 2021.

We hear frequently “I’m never going to forgive him that”, “don’t trust anyone”, “think wrong and you’ll get it right”… With the gospel in hand, knowing that it is a permanent call to fidelity, because Jesus, the Master, the Lord, forgave, trusted and did not have a negative f eeling towards anyone, we cannot accept distrust and suspicion as a norm of life, but it is understandable because we are human beings, and not robots programmed to act in a certain way.

We hear frequently “I’m never going to forgive him that”, “don’t trust anyone”, “think wrong and you’ll get it right”… With the gospel in hand, knowing that it is a permanent call to fidelity, because Jesus, the Master, the Lord, forgave, trusted and did not have a negative f eeling towards anyone, we cannot accept distrust and suspicion as a norm of life, but it is understandable because we are human beings, and not robots programmed to act in a certain way.

Many people pass through our lives, some stay, others simply pass by. Depending on where we may be and live, we see diverse human realities each day, and some of them require our attention for our work or coexistence in a common place or neighborhood, and other realities are outside our nearest day to day routine.

The areas of conflict or good understanding are variable according to our psychology, culture, age… There is a world in each of us different from that of others and, therefore, different ways of resolving or overcoming the difficulties of co-existence, family or community love, spirit of working together or the relationship of friendship.

If our life comes into conflict with one or more people, the workshop of our heart must produce a great deal of respect and responsibility, to place ourselves where we should be, with whatever dialogue is possible, understanding the reasons of others’ actions, without judging them. It is better to repair than to throw away. And if we close doors, we may ourselves be locked in, with the key on the outside.

because:

when we believe that a friendship is never going to break, and it is broken.

When we stand above anyone.

When we think we are better than others.

When in life we are weighed down more by failures than triumphs.

When we consider ourselves our own enemy.

When it hurts us that there are people who do not get involved as we do.

When we’re not mature enough to concede defeat,

then:

let us use the tool of humility, let us look at Jesus forsaken, wounded. Pope Francis said at the Chaldean rite Mass at St. Joseph’s Cathedral in Baghdad on March 6, 2021: “If I live as Jesus asks, what do I gain? Don’t I risk letting others lord it over me? Is Jesus’ invitation worthwhile, or a lost cause? That invitation is not worthless, but wise.“ And wisdom is the twin sister of humility.

If we find ourselves with situations in which, even having forgiven and forgotten, the workshop of our heart fails to make changes in our personal life or that of those who have moved away from our affection, from our fraternity, from our friendship and trust, from our welcome, we will feel defeat again… We cannot change others. Accepting the situation requires a degree of maturity that will leave us at peace with ourselves.

If we find ourselves with situations in which, even having forgiven and forgotten, the workshop of our heart fails to make changes in our personal life or that of those who have moved away from our affection, from our fraternity, from our friendship and trust, from our welcome, we will feel defeat again… We cannot change others. Accepting the situation requires a degree of maturity that will leave us at peace with ourselves.

When we regarded ourselves as “prodigal sons” of our brothers, and return to where we should never have said goodbye, when the other person was waiting for us, the workshop of the heart is free of old and useless junk, clean of the cobwebs of prejudices, letting things take their course, without victors or vanquished.

That I may be a brother to my enemy, with the inner joy not of having a quiet conscience for having done things as well as possible, but that which gives peace to the heart, that which charity and love repair, and then the joy that denotes the balance in our feelings will spring forth. A challenge, the challenge of Jesus who calls us to forgive seventy times seven and to be forgiven as many again.

Aurelio SANZ BAEZA

(Translation of Liam O`CUIV. Thank you!) (Boletín Iesus Caritas, 210)

(Italiano) Beati i poveri in spirito. Giorgio PISANO

(Italiano) Piccolli Fratelli Jesus Caritas, agosto 2021

Universal fraternity. Fernando TAPIA

Father Fernando Tapia

“YOU ARE ALL BROTHERS” (Mt 23,8)

-

FRATERNITY is at the heart of the Gospel. It is the novelty that Jesus brings in a very stratified society: divisions among slaves and free, wealthy very wealthy and poor very poor, absolute powers and peoples that are dominated by blood and fire, and among righteous and sinners, etc. Jesus is well aware of these ruptures in fraternity and implores his disciples to be different: “It shall not be so among you (…); whoever wishes to be first must become the servant of others” (Mt 20:27; see also Mt 23:8-11).

-

The seed of fraternity is at the core of Jesus’ evangelising practice: he engaged with tax collectors, the sick and sinners (Mk 2:15-17), he enters into dialogue with Samaritans (Jn 4:1-42), he allows himself to be questioned by a foreign woman (Mt 15:21-28), etc.; in other words, he breaks down the barriers that in his time separated human beings and he engaged with those who were despised and excluded, and generated in them a sense of joy and hope. At the same time, this engagement brought him into increasing conflict with those who wanted to keep in place the walls that separated human beings from one another: scribes, Pharisees and priests of the temple.

-

Through his closeness and compassion towards the outcasts of society of his time, Jesus wanted to make visible the foundation of human brotherhood: we are all sons and daughters of the same heavenly Father who “makes his sun rise on the good and bad and sends rain on the just and unjust” (Mt 5:45). In God’s heart there is no discrimination whatsoever. We are all loved by Him, whatever our moral situation.

-

St. Paul deeply understood this astounding message of the Gospel preached by Jesus and he would write to the Galatians in such audacious words: “By faith in Christ Jesus you are all children of God. Those who have been baptised and have consecrated themselves to Christ have put on Christ, so that there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:26-28). The Christian communities sought to this fraternity, that was surprising for Paul’s time. It was for this reason that they were attractive and multiplied throughout the whole Mediterranean basin. They were truly a “light of the world and salt of the earth” (Mt 5, 13-14).

-

For us, the sacrament of baptism marks the beginning of a life of fraternity. We receive the seed of fraternal life as a grace of sonship. However, we must cultivate it, otherwise it remains unfruitful. Though we are children of God, but we have to make ourselves children of God every day by seeking and doing the will of the Father. Though we are brothers and sisters (through Baptism), but we must make ourselves brothers and sisters by drawing near to one another each day, serving one another, forgiving each other up to seventy times seven.

THE RUPTURES OF FRATERNITY

-

To cultivate the culture of filiation, friendship and fraternity is an arduous task in our society that promotes and sustains a counterculture of individualism and competitiveness, selfishness and violence, discrimination and exclusionism, isolationism, and self-sufficiency. We just have to listen to and watch the news on television (and media).

-

As ministers of the Gospel we too can easily become infected with these viruses that circulate in our social and cultural environments and end of being “salt that loses its taste or a light that is placed under a piece of furniture” (cfr Mt 5, 13-15). However, what is expected of us by the Lord is exactly the opposite: “Let your light shine before men, that they may see your good works and praise your Father in heaven” (Mt 5:16).

-

The vaccine is to live out our ministry in fraternity, hopefully from the beginning of time of our initial formation in the seminary. It is an apprenticeship that purifies our love from selfishness, from being rigid and from the tendency to use others for our own benefit. It protects us from anguish, from bitterness, from hyperactivity, from psychosomatic illnesses and depressions, that is typical of those who always have to be number one in everything and to be so single-handedly.

-

If we are honest with ourselves, we must recognise that we cannot cope with life alone. We need others, we need companions for friendship, advice, comfort, and correction. There we can understand why Jesus begins his proclamation of the New Kingdom by forming a fraternity: The Twelve Apostles.

WHAT DOES A PRIESTLY FRATERNITY SEEK?

-

To grow together in the following of Jesus Christ. We gather together, like the disciples of Emmaus (Lk 24:13-35), to meet in the friendship of the Risen One, in the review of life, in the sharing of the Word, in prayer and in the breaking of the Bread.

-

To learn to be transparent, to trust others, to let others know about my family, my life, my money, my relationship with men and women, my sorrows, my need to be supported. To learn to love each other and to argue; to accept being different and not for that reason each one goes his own way. To be open to differences, to embrace their existence.

-

Learning to have a sense of belonging. To be with others and of others. It is not enough just to being, it is necessary to belong and to create links. It is about learning to carry (to take responsibility for) the lives of others. Learning to live and share with equals. To get out of the superior-inferior, dominator-dominated, protector-protected categories that are some of authoritarian traits that we all have.

-

This experience takes place in small groups (of 4 to 6 participants) so that everyone feels listened to, welcomed, accepted, and contained. We help each other to be faithful in the ministry entrusted to us and to walk together in the footsteps of Jesus, so that He becomes the centre of our lives, animated by His Spirit.

WHAT IS REQUIRED?

-

A decision to participate and join with others. It requires a decision to be real, to share what is really going on in our lives. It requires letting down our defences and letting ourselves being revealed. It requires confidentiality in all that we hear.

-

It requires that we participate in the monthly fraternity meeting which includes rest, food, worship, review of life, sharing the Gospel and sometimes the celebration of the Eucharist.

-

It requires stability in attendance as it takes time to build up bonds among participants. Accepting the frustrations that goes with all fraternal life: that others do not show up, that one would like to speak and there is no space or opportunity to do so, or that someone talks too much, etc.

-

It requires living with a sense of fraternity beyond the boundaries of the formal meeting, within the possibilities (day to day realities) of each priest. I am referring to such gestures as phone calls or visits to see how the other person is doing, birthdays wishes or greetings on the occasion of ordination anniversaries, being present when a new parish or another important assignment is undertaken, or having a fraternity outing.

CHARLES DE FOUCAULD, THE UNIVERSAL BROTHER

-

Our Priestly Fraternity has as its main inspiration the figure of Blessed Charles de Foucauld. We follow Jesus in the footsteps of this holy missionary. Like him, we would like to be passionate seekers of God and let ourselves be led by the Holy Spirit, wherever he wants to lead us. After his conversion, he became a Trappist monk, then an employee of the Poor Clare nuns and finally a diocesan missionary priest in North Africa. His desire was to imitate as closely as possible Jesus of Nazareth, his Brother and Lord, through a life of prayer, poverty and availability to all those in need.

-

Charles de Foucauld´s way of evangelising was universal brotherhood. In a letter to a friend, he replied: “Do you want to know what I can do for the natives? It is not possible to speak to them directly about our Lord. That would make them flee. We must inspire them with confidence, befriend them, render them small services, give them good advice, befriend them, discreetly exhort them to follow the natural religion, show them that Christians love them”. This is what he calls THE APOSTOLATE OF FRIENDSHIP. Perhaps some of us have had the experience of this way of evangelising non-believers, agnostics or those who are far from the Church.

-

In this way, our experience of priestly fraternity leaves us better prepared to be builders of fraternal life both within our presbytery and our Christian communities and at the social level. Brother Charles’ wayside shrine was always open to all and at all times. In a letter to his cousin Marie de Bondy he says: “I want to accustom all the inhabitants, Christians, Muslims, Jews, to look upon me as a brother. They are beginning to call my house ‘the fraternity’ and this is very dear to me”.

-

It is not surprising then that Pope Francis, who works tirelessly for universal fraternity, points out at the end of his encyclical Fratelli Tutti that Brother Charles was the main inspiration for this letter: “I would like to conclude by recalling another person of deep faith who, from his intense experience of God, made a journey of transformation until he felt that he was a brother to everyone. This is Blessed Charles de Foucauld (…) the universal brother”1.

-

I believe that the pandemic has given us the opportunity to discover and live universal fraternity through solidarity work. In our parish and in many parishes, we have worked side by side with believers and non-believers. Catholics, Evangelicals and Agnostics, have worked side by side to set up parish canteens and soup kitchens in order to deliver food baskets, toiletries and medicines etc. to the sick, the unemployed and the elderly. Also, they have networked with municipalities, health centres, social organisations, neighbourhood councils, etc.

CONCLUSION

-

We have believed in the words of Jesus: “You are all brothers” and we have tried to live it in our small priestly fraternities and to be builders of fraternity in our own environment. We do not want to be closed groups, simply of mutual help, who separate themselves from the others and think they are better than the others, like a priestly elite. We seek fraternal life because we know we are fragile and in need of others and because our world today needs to find ways of fraternity, as Pope Francis says in Fratelli Tutti. Our fraternity is always at the service of the Mission.

Santiago, Chile, July 2021

1 Pope Francis, “Fratelli Tutti”, n. 286 and 287.

PDF: UNIVERSAL FRATERNITY

A wrating about the fraternities. 1980

A Writing about fraternities probably from 1980,

An original contribution by a brother of the Spanish Fraternity

A SUMMARY of our exchanges

Charles de Foucauld wrote in Beni-Abbès in 1902: “I want to accustom all inhabitants: Christians, Muslims, Jews and pagans to look upon me as their “Universal Brother”.

This seemed to us to be an essential element of his message. How do we live it? Here are some important elements that can be drawn from our exchanges:

1) You cannot speak of universality without being rooted in a very specific milieu as was Jesus of Nazareth.

A deep encounter in friendship with a specific person puts us in communion with a whole milieu or a whole people By making ours the many sufferings of the poor, we join what is universal in the heart of man. Thus, it will be easy to encounter, in all situations, the universal man.

2) In our specific groups – fraternities, etc. we learn of universality in the operation of a diversity of temperaments, of ways of living, of situations, of options, etc. One does not choose one’s brothers, one’s sisters, Similarly, in a family, parents must accept the diversity of their children. Knowing how to listen, seems absolutely essential in order to accept the other in his or her uniqueness.

3) For this acceptance to be authentic, it must be deepened in truthfulness and in clarity, so that each one is recognized and accepted in what he or she is, in their own destiny or commitment, however extreme it may seem to us. An in depth “Review of Life” is necessary in order to orient oneself in the face of the common vocation of our group.

4) Desiring to live Universality is often done in suffering, because it entails misunderstandings and ruptures, the meeting of obstacles and tensions, and seeing impossible situations. How can someone love the rich when he suffers with the poor? How in a specific case do you reach forgiveness? Just as when one feels one’s impotence in the face of the world’s enormous problems.

All this compels us to live Universality with hope, propelled in prayer. When everything is beyond us, it is the time to ask God that He accompany my brother.

5) Universality is not natural. It only comes to us through Christ; it is in Him that we find the unity of all people. In prayer barriers are abolished. The Eucharistic prayer and the offering of suffering, in union with the redemptive mystery, have an efficacy of universal scope.

6) A universal action is impossible. Yet our heart must become universal: all men are our neighbour, our responsibility is committed to each one.

To be universal is not only respect for the other, the poor, the non-Christian, more especially our Muslim brother, but it is the humility that allows us to learn from the other, to be transformed and evangelized by him.

We are tempted by self-sufficiency, which prevents us from renewing our human relationships, and from feeling that one has an incessant need for others.

We will have the illusion of believing ourselves to be universal because we have a vast information: intellectual culture is not enough, humility and realism are necessary.

The Responsibles of the Fraternities

(Translation of Liam O’CUIV. Thanks so much)

Great powers hold umbrella over coup in Myanmar. Arne WILLEMS

Tertio, 14 july 2021 (Flanders/Belgium Religious weekly)

The situation in Myanmar has completely escalated since February. The army deposed the government of Aung San Suu Kyi and arrested her for numerous alleged offences. Since then, a civil war has been raging, with fighting taking place in quick succession. After an attack on a church, Pope Francis called for religious sites to be banned, a call that so far has fallen on deaf ears. Myanmars specialist Walter Mensaert sheds his light on the conflict.

Walter Mensaert is an experienced travel agent who has specialised in Myanmar – the former Burma – for more than a quarter of a century. As a travel agent, he has good contacts in the Asian country and its neighbouring countries. Through local correspondents and news sites, he follows the situation in Myanmar closely. “More than 25 years ago, we focused on a few Asian countries. After a few visits to Thailand, Burma caught our eye. The purity of Myanmar contrasted sharply with the commerciality of the neighbouring countries. This authenticity is typical for the country. But it is also very unstable, it has been in civil war for over 70 years: the longest running in the world. Since my first visit in 1995, Myanmar has had good periods, but also many dark periods, and the darkest is now upon us”, Mensaert believes.

“Myanmar has seven states where ethnic minorities are dominant and seven more central regions where the Bamars, the original inhabitants, make up the majority of the population. Many rules and laws discriminate against non-original Burmese. For example, people from these minorities cannot climb to high positions in the army or to important civil service positions: these are reserved for authentic Burmese. The government of Aung San Suu Kyi has tried to change this and has put more emphasis on equality. This led to a large protest from the army”.

The army is now in power after a military coup. Why are government and army diametrically opposed?

“You cannot compare the army in Myanmar with what we know in Belgium as Defence. Here the army is paid by the government, in Myanmar the army generates more income than the government. They get their income from the export of raw materials: gems, jade, gas and oil. That money gives the army great power and causes a power struggle between army and state. Many soldiers are conservative, nationalistic Burmese, who oppose foreign population groups. There is also a conservative movement of monks, who only want Buddhism in Myanmar. Both movements have tolerated other population groups and religions for years, but that seems to have come to an end.”

There have already been several attacks on Christian targets in Myanmar. Is there any persecution of Christians?

“The Catholics are found mainly in Kayah, Chin and Kayin state. In Kayah State – the region where the longnecks live – there is heavy fighting now. This is not persecution of Christians. It is a power struggle between the army and the minorities, an attempt to push through their nationalist agenda. The violence is not aimed specifically at Christians; the Rohingya, the Muslim minority, are also suffering. One of the important factors is the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya from Bangladesh. They are no longer a minority in Rakhine State, which has caused unrest among the population and the authorities.”

The war in Myanmar is still raging, but reports are only trickling in sparsely. How do you explain that?

“Reporting is a big problem. Because the country has been in turmoil for decades, the books that are published are historically incorrect. This makes it very difficult for the outside world to understand the problems in Myanmar. A lot of fake news appears, which makes the situation even more difficult. I follow Al Jazeera, BBC and some international news agencies closely, but reports are scarce. Just at this moment, eye-catching advertisements are circulating for Burmese YouTube viewers. One of my correspondents – someone I have worked closely with for 26 years – sent a commercial: ‘My friend, I know you are full of trapped feelings and words that you would like to express, but don’t know who to talk to. You can talk to me. I am your friend, Jesus’. The impact of such messages on the spread of Catholicism, especially among frightened

and searching young people, cannot therefore be underestimated.”

The conflict has been dragging on for decades. Why did the fire go out on 1 February?

“Covid-19 was the trigger, I think. There were no more tourists in the country, the economy was hit hard and the army seized that momentum to close all airports and carry out the coup. The accusations against Aung San Suu Kyi are ridiculous: among other things, she was arrested for not wearing a mouth mask. February is normally the tourist high season, now – in the absence of tourists and international attention – it was marred by the events of February 1.”

What is the situation in the country now?

“The coronavirus is currently raging very fiercely in Myanmar. Millions of residents are out of work due to an economy in free fall. Hundreds of thousands fled the violence into the forests. The military is playing a dirty game (sigh). They work with informants and have appointed a government official in each district. In this way, they exert pressure on and control over the population, which rebels against these measures. Peaceful protests are brutally suppressed. There are regular reports from Catholic quarters: a sister kneeling before a soldier on the road and begging for peace, an attack on a church, the arrest of priests who were calling for peaceful protest. Even Pope Francis called on the regime to keep religious places free from violence: a call that fell on deaf ears.”

Myanmar is always on the border between war and peace. Is there a brightening in the near future?

“It is a very delicate situation. With an oil pipeline and silk route running through Myanmar, there are international interests at stake in the country’s political development. The surrounding superpowers are interfering in the conflict in a negative way, mainly through trade interests. Some supply weapons, others have a pipeline running through the country. The population is now turning against China: there have already been several attacks on Chinese factories. The representatives of the United Nations have tried to engage in dialogue, but without result. As long as the interested superpowers keep their umbrella over the military junta, the situation seems hopeless.” III

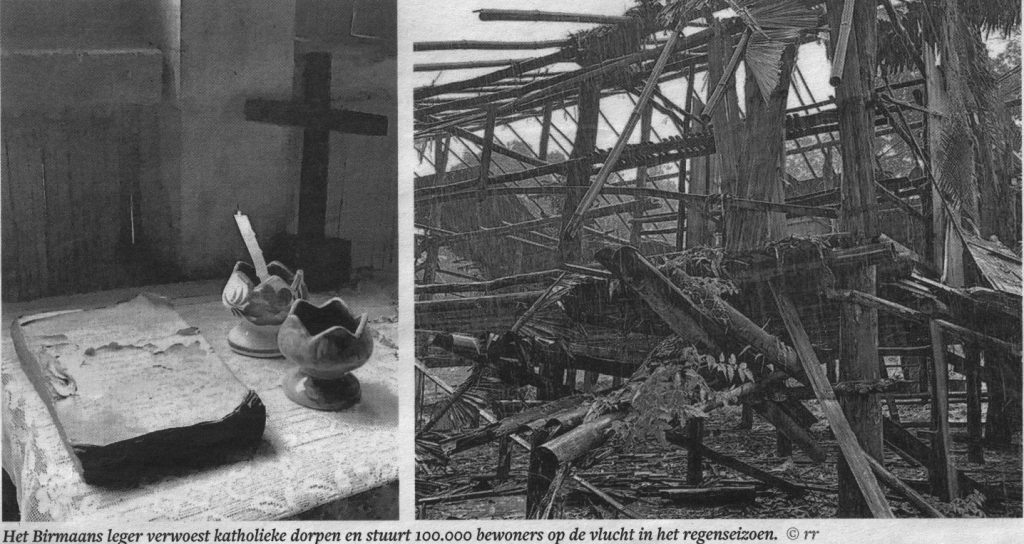

The Burmese army destroys Catholic villages and causes 100,000 people to flee during the rainy season.

The Burmese army destroys Catholic villages and causes 100,000 people to flee during the rainy season.

PDF: Great powers hold umbrella over coup in Myanmar. Arne WILLEMS en